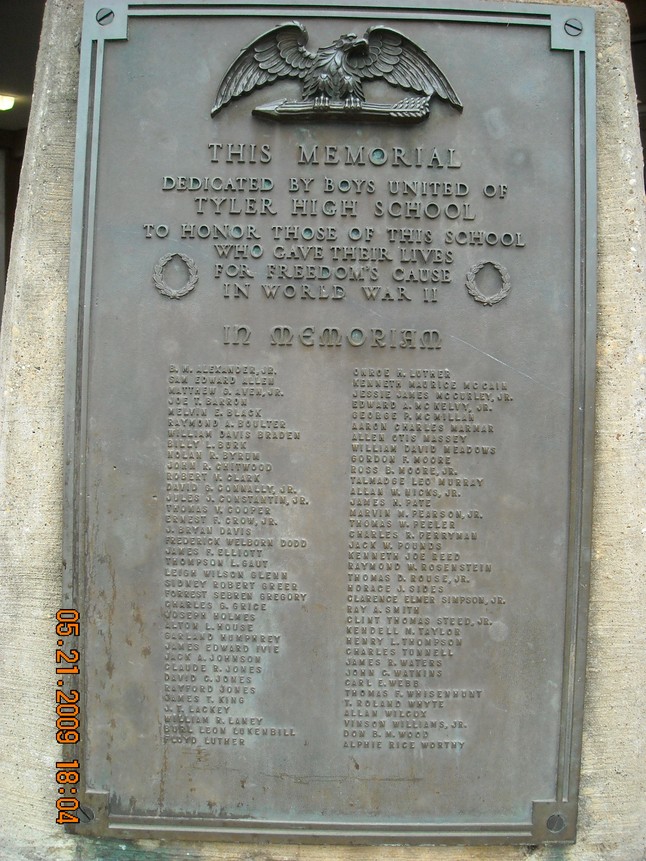

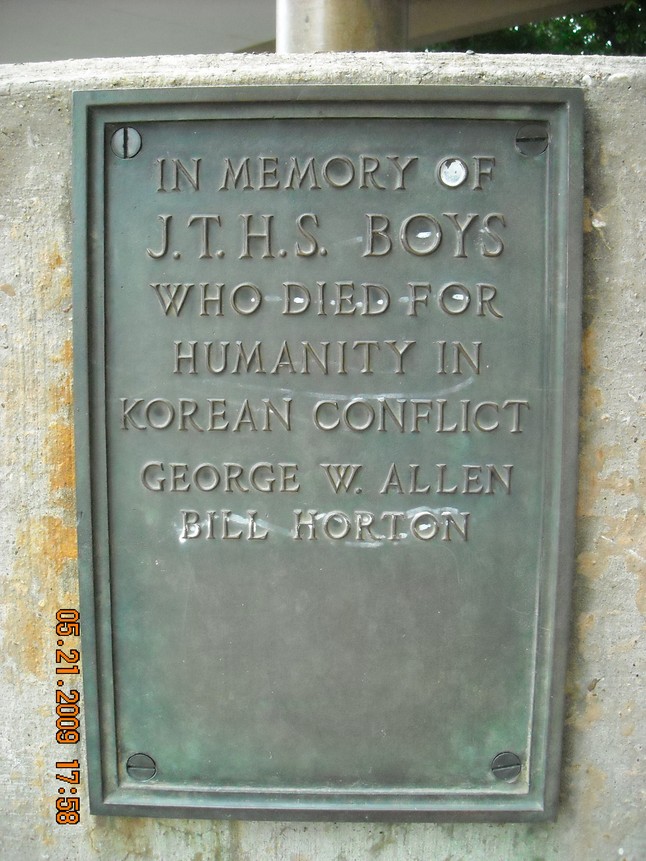

John Tyler High School

Tyler,Texas

Class Of 1968

Memorial Day

Memorial Day is a day for reflection. With that in mind, I have collected various photos, articles, poems, song lyrics, essays, and journalistic odds and ends that reflect on the meaning and history of this day. As the designation indicates, it is a time for remembering.

In deepest gratitude, we pause on Memorial Day to remember our loved ones, our ancestors, and our friends who gave their lives in our nation's conflicts and wars - not to honor war, but rather those who died in honorable service. We hope that you, your family, and friends enjoy a safe Memorial weekend and that you'll take a few moments to read this before you start your barbeque, picnic, or family dinner.

"Gather around their sacred remains and gardland the passionless mounds above them with the choicest flowers of springtime.....let us in this solemn presence renew our pledges to aid and assist those whom they have left among us as sacred charges upon the Nation's gratitude - the soldier's and sailor's widow and orphan." General John Logan, General Order No. 11, May 5, 1868

The dead at Gettysburg.

Memorial Day History & Meaning

The First Cause

Here are some excerpts from a NY Times editorial by Adam Cohen.

Memorial Day got its start after the Civil War, when freed slaves and abolitionists gathered in Charleston, S.C., to honor Union soldiers who gave their lives to battle slavery. The holiday was so closely associated with the Union side, and with the fight for emancipation, that Southern states quickly established their own rival Confederate Memorial Day.

Over the next 50 years, though, Memorial Day changed. It became a tribute to the dead on both sides, and to the reunion of the North and the South after the war. This new holiday was more inclusive, and more useful to a forward-looking nation eager to put its differences behind it. But something important was lost: the recognition that the Civil War had been a moral battle to free black Americans from slavery.

War commemorations do not just pay tribute to the war dead. They also reflect a nation’s understanding of particular wars, and they are edited for political reasons. Memorial Day is a day not only of remembering, but also of selective forgetting — a point to keep in mind as the Iraq war moves uneasily into the history books.

Many of the early Memorial Day commemorations were like Charleston’s, paying tribute both to the fallen Union soldiers and to the emancipationist cause. At a ceremony in Maine in 1869, one fiery orator declared that “the black stain of slavery has been effaced from the bosom of this fair land by martyr blood.”

Less than a decade later in 1877 — when Reconstruction ended in the South — at New York City’s enormous Memorial Day celebration, there was much talk of union, and almost none of slavery or race. The New York Herald declared that “all the issues on which the war of rebellion was fought seem dead,” and noted approvingly that “American eyes have a characteristic tendency to look forward.”

There were dissenting voices. Frederick Douglass, the great abolitionist leader, continued to insist that Memorial Day should be about the battle between “slavery and freedom, barbarism and civilization.” But the drive to make the holiday a generic commemoration of the Civil War dead won out.

The new Memorial Day made it easier for Northern and Southern whites to come together, and it kept the focus where political and business leaders wanted it: on national progress. But it came at the expense of American blacks, whose status at the end of Reconstruction was precarious. If the Civil War was not a battle to determine whether a nation “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” could “long endure,” as Lincoln declared in the Gettysburg Address, but a mere regional dispute, there was no need to continue fighting for equal rights.

And increasingly the nation did not. When Woodrow Wilson spoke at Gettysburg on the 50th anniversary of the battle, in a Memorial Day-like ceremony, he avoided the subject of slavery and declared “the quarrel” between North and South “forgotten.” The ceremony was segregated, and a week later Wilson’s administration created separate white and black bathrooms in the Treasury Department. It would be another 50 years before the nation seriously took up the cause of racial equality again.

Since 1913, Memorial Day has changed even more. It has expanded — after World War I, it became a tribute to the dead of all the nation’s wars — while at the same time fading. Today, Memorial Day is little more than the start of summer, a time for barbecues and department store sales. Much would be gained, though, by going back to the holiday’s original meanings.

When Memorial Day began, the war dead were placed front and center. The holiday’s original name, Decoration Day, came from the day’s main activity: leaving flowers at cemeteries. Today, though, we are fighting a war in which great pains were once taken to hide the Americans who died there from sight.

Memorial Day also began with the conviction that to properly honor the war dead, it is necessary to honestly contemplate the cause for which they fought. Memorial Day’s history, and its devolution, demonstrates that the instinct to prettify war and create myths about it is hardly new.

But as the founders of the original Memorial Day understood, the only honorable way to remember those who have lost their lives is to commemorate them out in the open, and to insist on a true account.

The Final Cost

Here is a short essay by Terry Plowman.

Memorial Day now suffers the same secular fate as Christmas -- its commercial value has far outstripped its original meaning. That fact is especially evident here in a resort area, where Memorial Day weekend is considered the kickoff to the busy summer season.

Although there is nothing terribly wrong with that, and we couldn't change it anyway, we hope readers will give a few moments thought to the real meaning of Memorial Day this weekend. The trouble with evoking memories from past military conflicts is that it is like looking at a grainy black-and-white photograph or newsreel (an outdated term in itself).

For many Americans who can barely remember life without color photography, looking at these black-and-white images has little impact. They represent another time, one that is hard to connect with today. But for those who lived through the past few wars, there is color in the memories, and for many of those who served in the military, the color is blood red.

For them Memorial Day is not a history lesson, quickly forgotten like other lessons from our school days. For them it is the father, the brother, the son, the husband, the pal who never came home. And for those of us living today, the war dead are our vivid connection to Memorial Day -- because it is an eerie fact that many of us would not be here today were it not for a quirk of fate that allowed our fathers to survive a war.

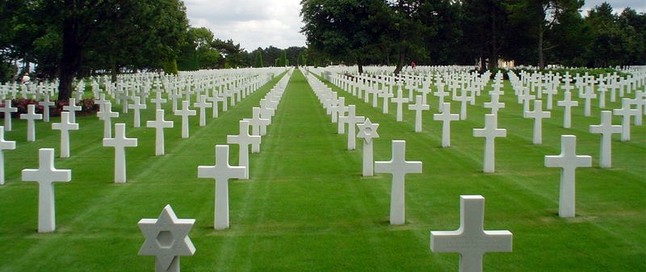

How many of the more than 400,000 World War II dead would have fathered the geniuses, the creators, the liberators of today's generations? How many of the 116,000 World War I dead, the 54,000 Korean War dead, or the 58,000 Vietnam War dead? How many of the 500,000 Civil War dead would have fathered children whose impact would still be felt in our lives today?

Actually, many of these dead patriots were themselves only 18 or 19 years old, so they were robbed of the chance to leave us any legacy other than the memory of their sacrifice. A wounded seaman who was taken aboard a rescue vessel during the D-Day invasion was quoted in Life magazine about the fundamental mystery of war:

"(The ship) was loaded with the bodies of sailors, soldiers, airmen; the wounded and survivors. And on board was the body of my friend Pete Petersen. He was going to be 21 on June 22. One thing you always wonder is, who makes that decision: Who dies and who doesn't?"

On this holiday weekend, let's not forget the meaning, the mystery and the tragedy behind Memorial Day.

Arlington National Cemetary

Taps

Of all military bugle calls, none is so easily or emotionally recognized as "Taps." The haunting 24-note melody originally began before the Civil War as a revision to "Extinguish Lights," the lights-out signal at the end of the day.

The first use of "Taps" at a funeral came during the Peninsular Campaign in Virginia in 1862. Captain John C. Tidball of Battery A, 2nd Artillery, ordered it played for the burial of a cannoneer killed in action. It was unsafe to fire the customary three rifle volleys over the grave on account of the enemy's proximity. So it occurred to Captain Tidball that the sounding of "Taps" would be the humble ceremony afforded this fallen hero. The new custom quickly spread throughout the Army of the Potomac and even in the Confederacy.

Taps was played at the funeral of Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson 10 months after it was composed. Army infantry regulations by 1891 required taps to be played at military funeral ceremonies.

Taps now is played by the military at burial and memorial services, to accompany the lowering of the flag and to signal the “lights out” command at day’s end.

Here are some links pertinent to this section:

1. Memorial Day History and Information on Wikipedia; link:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memorial_Day

2. Arlington National Cemetary on Wikipedia; link:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arlington_National_Cemetery

The War That Didn't End All Wars

For most of the remaining countries in the world, recognition of those who died in service to their country is held on November 11th when we celebrate Veterans Day here in America. It is often called Remembrance Day. Because the First World War is considered one of the most unnecessary and horrible wars of all time, Remembrance Day does not flinch from the fact of dying while it pays homage to the deeds of those who died.

From the novel Company K by William March

“You can always tell an old battlefield where many men have lost their lives. The next Spring the grass comes up greener and more luxuriant than on the surrounding countryside; the poppies are redder, the corn-flowers more blue. They grow over the field and down the sides of the shell holes and lean, almost touching, across the abandoned trenches in a mass of color that ripples all day in the direction that the wind blows. They take the pits and scars out of the torn land and make it a sweet, sloping surface again. Take a wood, now, or a ravine: In a year's time you could never guess the things which had taken place there.

I repeated my thoughts to my wife, but she said it was not difficult to understand about battlefields: The blood of the men killed on the field, and the bodies buried there, fertilize the ground and stimulate the growth of vegetation. That was all quite natural she said.

But I could not agree with this, too-simple, explanation: To me it has always seemed that God is so sickened with men, and their unending cruelty to each other, that he covers the places where they have been as quickly as possible.”

Canadian poet John McCrae was a medical officer in both the Boer War and World War I. A year into the latter war he published in Punch magazine, on December 8, 1915, the sole work by which he would be remembered. This poem commemorates the deaths of thousands of young men who died in Flanders during the grueling battles there. It created a great sensation, and was used widely as a recruiting tool, inspiring other young men to join the Army. Legend has it that he was inspired by seeing the blood-red poppies blooming in the fields where many friends had died. In 1918 McCrae died at the age of 46, in the way most men died during that war, not from a bullet or bomb, but from disease: pneumonia, in his case.

In Flanders Fields by John McCrae

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Here is a link to a Wikipedia article on Remembrance Day:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remembrance_Day

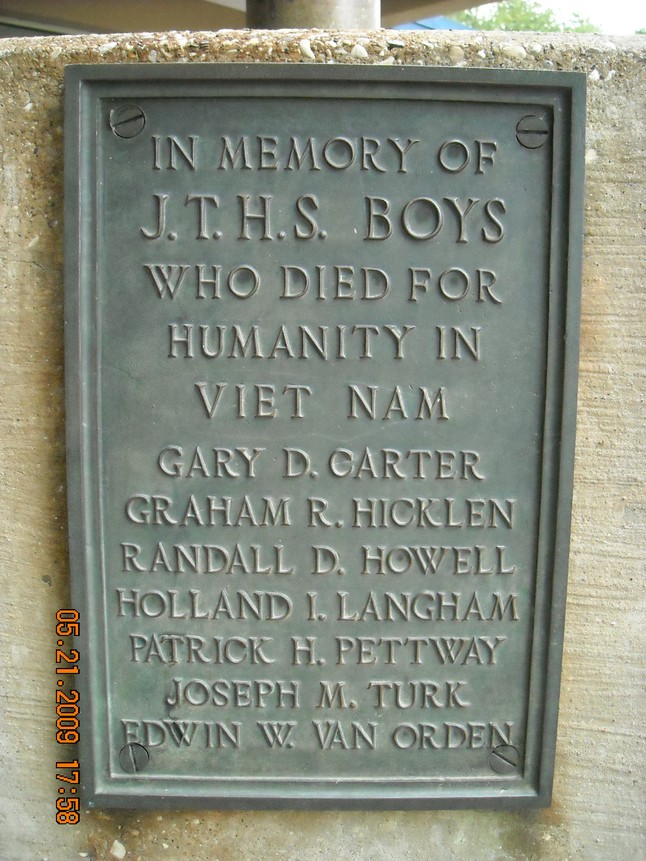

Vietnam

This was our generations war and it still affects us today. We have all become survivors of this war.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall

The Wall website link:

If you would like to see a list of the Tyler dead who are listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall, follow these directions to use the link below. Other searches are possible, if you wish.

Directions: Click on Search the Wall. We used Tyler as Home of Record and Texas as the State and got a list of about 30 names. When you click Start Search you will get your list. There are 10 names per page. Each name gives some basic information plus provides a link to that person's INFO PAGE where they give his time in Vietnam, date of death, and reason for death. From here you can link to Personal Comments and write something about that person or read other comments placed there by family, friends and comrades.

The song "Rooster" by Alice in Chains

Ain’t found a way to kill me yet,

Eyes burn with stinging sweat,

Seems every path leads me to nowhere.

Wife and kids, household pet,

Army green was no safe bet.

The bullets scream to me from somewhere.

Here they come to snuff the rooster, oh yeah.

Yeah, here comes the rooster,

You know he ain’t gonna die.

No, no, no, you know he ain’t gonna die.

Walking tall, machine gun man,

They spit on me in my homeland,

Gloria sent me pictures of my boy.

Got my pills ‘gainst mosquito death,

My buddy’s breathing his dying breath,

Oh God please, won’t you help me make it through?

Here they come to snuff the rooster, oh yeah.

Yeah, here comes the rooster,

You know he ain’t gonna die,

No, no, no, you know he aint’gonna die.

On 9 January 2009, Danny Jones wrote:

Guess what today is for me? Want to guess? Not a clue, huh? Well, I will tell you. Forty years ago today I went to the NAM. Yep, flew out of Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma 40 years ago today. About 27 hours later, I was in Pleiku Viet Nam.

Ah well, time flies, don’t’ it! At least I came back. But don’t tell me “Welcome Home.” I never got home. I left a BIG part of me over there. I never will get me back. Maybe someday I will go back and look for me. If you see me, tell me hello and hurry home. Tell me I was missed, and that I wasn’t a ”Baby Killer.” I only did as my Country asked of me.

Tell me it is OK to forgive me. I only wanted to keep me and my buddies alive. Tell me it’s OK to cry and feel alone. Tell me it’s OK to be a loner, as I don’t know me after that war. Tell me it’s OK to be me again. I sure want to be me, but I’m not really sure who the real me is. Anyone know the real me? Please introduce me to me.

The Thousand Yard Stare

Vietnam Veteran Gary Jacobson's "My Thousand Yard Stare," was awarded the inaugural "Top Poet Bronze Helmet Award," from the "International War Veterans Poetry Archive." Click on the link below if you would like to read it.

Death and Other Distractions

The Language of Death

Western society has long had its favorite euphemisms for avoiding expressing such an ultimate action as death. This Orwellian double-speak is a regular part of our lives or, I should say, our deaths. We seem to want to distance ourselves from the reality of the loss, making it abstract, applicable to others and not ourselves.

Common euphemisms to avoid saying “dead”: Passed away; Passed on; Gone to a better place; Departed; Gone to meet the Maker; Gone to meet the majority; Gone to the world of light; Gone to Davy Jones’s locker; Crossed to the other side; Gone to sleep with the fishes; Quietly slipped from our embrace; Succumbed; Called home; Got her/his final reward; Expired; Dearly departed.

The criminal world has its own set of avoidances of the reality of death such as: whacked, smoked, wasted, rubbed out, deep sixed and given cement overshoes.

Finally, there’s the humorous and sardonic: croaked, gave up the ghost, put on the wooden overcoat, total goner, kicked the bucket, dead as a doornail, snuffed it, bit the dust, bought the farm, flat-lined, became a landowner, is pushing up daisies.

Survivor's Guilt

From the book Human Adaption to Extreme Stress by John Preston Wilson, Zev Harel, Boaz Kahana

“Combat invariably produces feelings of shame and remorse in survivors. The untimely and traumatic death of friends and comrades haunts those who pull through the experience with the unanswerable question, 'Why was I spared?'”

Citing other authors on the subject, “death guilt may be the survivor's greatest psychological burden” and “combat veterans often believed that they, not their buddies, should have died.”

“Men with postwar problem experienced more war-related social losses (i.e., friends captured, injured, or killed) than other veterans. Overall, two out of three men with emotional problems lost friends in the war.”

SURVIVOR’S GUILT by Cloy Richards USMC

(In Honor of My Friend Jeffrey, who died at Camp Fallujah)

I stare at this paper and I don’t know what to say.

I don’t feel right saying“Happy Memorial Day.”

I don’t find anything happy in the price we pay.

We are both just pawns when this game of war is played.

My body came home but my spirit just stayed.

That hot Iraqi day that you were slayed.

Watching my back so I could sleep unafraid.

I heard the explosion from where I laid.

And instantly I watched all the skies go gray.

I watched my life just float away.

How could things go this way?

You were my brother-in-arms and you took my place.

But not the way that car bomb took your face,

and blew off your limbs.

When I think about it my head starts to spin.

I get nervous when I think of your family.

I want to tell them, I truly am sorry.

I’m sorry your son died protecting me.

This isn’t the way things were meant to be.

You see that day your son took my duty.

Your brother sacrificed his four hours of sleep,

so he could guard the gate for me.

I’m sorry your father took my place for me.

I’m sorry I can spend Memorial Day with my family.

Today should have been for you, not me.

From an anonymous vet

As a vet, I am compelled to remind those who blithely celebrate Memorial Day as just another chance to get away from work and to have a little free time that you ought to spend a few moments contemplating those who've paid the ultimate price.

Some may ask you to remember a cause that the war was fought over and can point to the Civil War and World War II as leading examples of just causes. I simply ask you to also remember what terrible things war has caused. Rather than focus on the noble idea of sacrifice, I wish to remind you of what was done to these unfortunate ones when they made their sacrifice.

Last century and up to now, hundreds of millions of men (and many women and children) were shot, bayoneted, bludgeoned, stabbed, bombed, grenaded, gassed, incinerated by flamethrowers or burning fuel and oil, choked, drowned in oceans or shell craters, smothered in caved-in trenches, obliterated by mines, blown to pieces by artillery shells most often, and getting killed in countless other ways devised by so-called civilized human beings.

War is a bloody, cruel, and ghastly enterprise. That is a lot of rotting corpses and inhumane horror that politicians would rather not have you remember when thinking about this day.

Homecoming

“Bringin’ Buddy Home” by John McDermott

Somewhere between earth and heaven

The C-17 flies,

Heading westward homeward

Through clean, clear, safe blue skies

At the back of the airplane

Lying alone

Draped in his country’s flag

They’re bringing Buddy home.

Somewhere between tears and heartbreak,

A lifetime sorrow just begun

Grieving, disbelieving,

As parents wait to welcome home their son.

And pray for the strength

Somehow to face the days ahead

While heading westward homeward,

The Nation’s bringing home its dead.

When the rifles fire the volley

At the word of command

When they fold up Old Glory

And they place it in your hand

You can cry then,

And say goodbye then,

For Buddy’s now a name on a cold marble stone

And he’s never, never, never coming home.

Somewhere between fear and hatred

The black heart of war lies

Growing blacker, stronger,

With every young man who dies.

Far back from the airfield,

At their post in the combat zone,

His comrades wonder,

Who’ll be the next one going home.

When the rifles fire the volley

At the word of command

When they fold up Old Glory

And they place it in your hand

You can cry then,

And say goodbye then,

For Buddy’s now a name on a cold marble stone

And he’s never, never, never coming home.

Remember

This poem is by Malcolm Watts and it seems an appropriate way to close our thoughts by recalling all who stepped forward to serve their country.

Remembrance

.JPG)